A Conversation with Barbara Ubaldi, Head of the OECD's Digital Government and Data Unit

Thought Piece #21 The OECD's lead on digital technologies talks context-led design, open data portals and regional cross-border data flows

During the 15 years that Barbara Ubaldi has headed up the OECD’s Digital Government and Data Unit, much has changed in the way that governments approach technology. As she puts it herself, the most proactive governments have moved from thinking about e-government to digital government. More specifically, they have shifted their ambitions from digitizing existing services to catalyzing a whole-of-ecosystem shift towards better designing and delivering public services. “A digital government is one that goes beyond moving processes and procedures online”, she told Eurocities last year, “and really tries to change how it functions to deliver better value”.

As we begin our interview, she strikes a largely similar tone. “To be user-centered, there is a whole universe of changes that you need to put in place”. Cue a collective gulp from civil servants. But fortunately, as digital government has evolved, so has the capacity of organizations like the OECD to support them. Today, the OECD has become the multilateral go-to for knowledge papers and compendia of digital government initiatives, and the developer of a major digital government index. A cursory glance at its website will reveal recent profiles of Turkey, Thailand and Slovenia, to name just a few.

It is with the role of multilateral bodies in the digital government ecosystem that we start, or more specifically, how each manages to complement the others in avoiding the duplication of work. The OECD is not the first intergovernmental organization (IGO) that Ubaldi has worked for – she spent a number of years at the UN beforehand. The difference between the two is both in structure and activity, she tells me. The OECD’s membership – 38 of the world’s most advanced democratic economies – are often like-minded on digital government (and other) issues. The focus is therefore much more on sharing relevant good practice between each other, rather than trying to find consensus and common ground.

This membership structure informs the OECD’s mandate, with its focus on producing knowledge and normative initiatives. Unlike a body like the European Union (EU), the OECD normative instruments do not have to be translated by national governments into national legislations, but governments often commit to implementing them nonetheless. In contrast, the UN’s various bodies are able to work much closer to the ground, and take the lead on tackling challenges like digital development.

Being a smaller membership organization leaves the OECD, at least in theory, susceptible to a common accusation levelled at international digital government lesson-sharing: the idea that success in the space is predicated on the so-called “Scandinavian model”. Solutions that work in small, liberal democracies (a category to which many of the OECD’s member states belong) do not necessarily translate elsewhere, or so the argument goes. With 9 out of the top 20 global GovTech leaders (as per the latest UN eGov Development Index) having populations of less than 6 million, it is a valid concern. I ask Ubaldi how the OECD guards against this in assembling models of good practice for their guides and handbooks.

Naturally, the simple answer – that the OECD works “context first” – hides a much more interesting philosophy of digitalization. Digital government success is inextricable from the contexts in which it was formed, Ubaldi tells me: Estonia could not have been so successful if it had had pre-existing legacy technology; the UK’s GDS could only work because of the backing of Francis Maude; and Korea’s strength in breaking down silos is only possible because of its centralized governance model.

But there is also a danger that contexts become exclusionary. Take conversations around artificial intelligence, and particularly Generative AI. Governments around the world are under pressure to develop use cases for AI, with many potentially game-changing initiatives coming out of Europe and Asia. At the same time, as Iceland’s Andri Kristinsson told interweave, not all countries are ready to have these discussions. The question becomes how to have timely and context-driven conversations on AI regulation in a way that does not go over the heads of the countries yet to prioritize it.

In many ways this is a question of the form of discussions, and the OECD’s reliance on case studies is to a large extent an attempt to mitigate this challenge. Structuring conversations and recommendations around specific examples grounds potentially theoretical discussions in real world contexts. Countries who have not yet employed AI are then able to apply the OECD’s contextual framework – which looks at a country’s national context; institutional models; and policy levers – to these examples.

Solving Problems Across Borders with Open Data

Conscious that Ubaldi’s OECD remit includes not just digital government services but data as well, we shift our discussion elsewhere. In the same Eurocities interview last year, she noted that “the main challenges [to digital government] are not technical - which is, on its own, a challenge”. Cultural transformation is chief on her wish list for governments, and a shift towards open data a priority within this cultural transformation.

The OECD defines open government data as “a philosophy – and increasingly a set of policies – that promotes transparency, accountability and value creation by making government data available to all”. As Ubaldi puts it, “when the big data splash happened, governments realized that they were sitting on very important data”. This data has the potential to help governments be more transparent, proactive, and effective and many – including the OECD and interweave’s previous interviewees – argue that this asset should be made available as a public good.

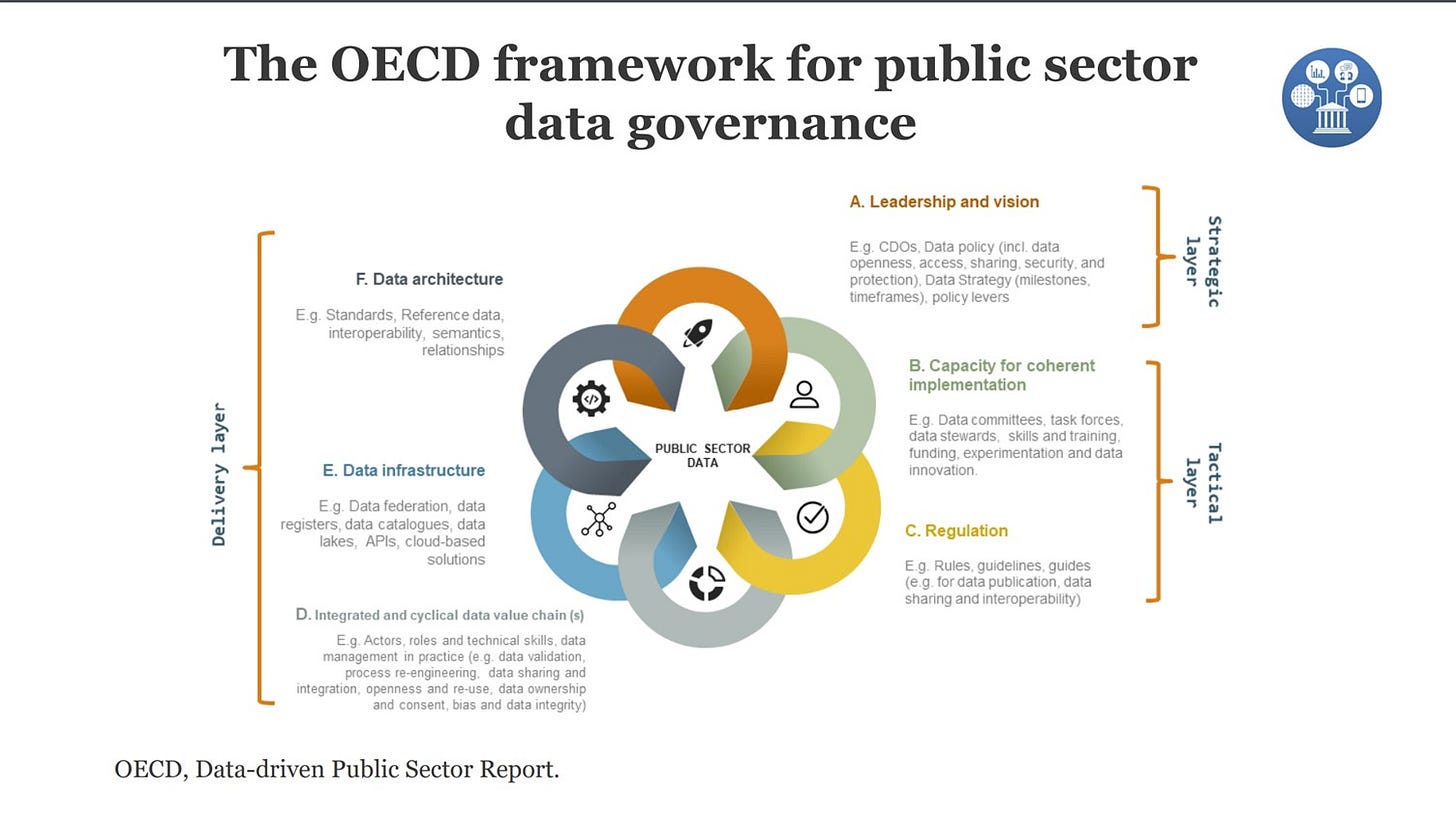

Source: OECD, Data-driven Public Sector Report

Cross-border data flows have been particularly newsworthy this year, with Japan prioritizing them as part of their G7 summit. For Ubaldi, this is the future of international digital government collaboration. With open datasets, countries will be able to better coordinate efforts in a number of policy areas including immigration, and – as Ubaldi puts it – “people who study a problem in country A can produce tomorrow’s solution in country B”. She gives the example of France, whose National Digital Strategy highlighted the importance of open government data as early as 2016. Data.gouv.fr, the country’s open data portal, allows citizens and organizations to comment on datasets, and even publish their own. The country ranks second in the world on the OECD’s Open Government index, scoring highly on all three of the data availability; accessibility and reuse dimensions.

Now, Luxembourg and Finland are adopting similar models, laying the foundations for greater cross-border collaboration between these countries. They are not the only ones. Latin America – from which Mexico, Chile, Costa Rica and Colombia are OECD member states – are also prioritizing open data as a region, using a shared asset declaration register to tackle corruption. As I think back to interweave.gov’s previous guests – to Ireland’s Tony Shannon and his diaspora services, or Jigme Tenzing and Bhutan’s digital ID-driven passports – it is clear how important scaling this collaboration could be. Ubaldi’s team, and the OECD more generally, will no doubt be crucial in enabling this.